Gründerzeit

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

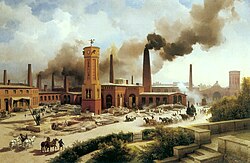

The Gründerzeit (German pronunciation: [ˈɡʁʏndɐˌtsaɪt] ⓘ; lit. 'founders' period') was a period of European economic history in mid- and late-19th century Germany and Austria-Hungary between industrialization and the great stock market crash of 1873. Its name is derived from the many incorporations of companies that occurred in the years between the Franco-Prussian War and the panic of 1873.

The term also refers to a cultural and architectural era which began in the mid-19th century and lasted until 1914. Gründerzeit architecture is closely associated with historicism, and occupies a prominent place in many Central European cities due to 19th-century urbanization.

Periodization

[edit]Social and Economic History

[edit]The years constituting the economic Gründerzeit are not universally agreed-upon. In the most narrow sense, the term refers to the two years following the founding of the German Empire in 1871 (also called the Gründerjahre, or "founder's years"), in which French war reparations from the Franco-Prussian War charged massive growth and speculation.[1][2] Some economists have postulated that the era began in 1869, a year in which corporate law and the Handelsgesetzbuch were liberalized across Germany.[3][4] Others put the beginning of the period in the 1860s, or earlier, while most agree on the 1873 end-date.[5][6] Alternatively, German historian Christian Jansen delineates the period as lasting from the Revolutions of 1848 to the founding of the German Empire.[7] Nikolai Kondratiev described the economic upswing in which the Gründerzeit occurred as the growth phase of the second Kondratiev cycle.[8]

Art and Cultural History

[edit]Industrialization and urbanization opened new stylistic frontiers, especially in architecture. However, industrialization's rapid and drastic changes also engendered a reaction, with many artists and members of the bourgeoisie turning to history and tradition (see romanticism). This resulted in an eclectic development of existing forms.[9] "Gründerzeit style" is a term often inseparable from historicism. Because historicism remained a predominant style until after 1900, the delineation of this art-historical era is imprecise.[10] In the context of stylistic history, it can refer to varying periods within the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as 1850–1873, 1871–1890, and sometimes even 1850–1914. The distinction of the Gründerzeit from other periods (such as the Belle Époque) is not delineated.

Economy

[edit]

According to conservative definitions, the Gründerzeit was a very short-lived, but extraordinarily productive economic boom at the beginning of the German Empire. Hundreds of new businesses, banks and railways were founded in the few years assigned to the period.[6] The founding of joint-stock companies was crucial to the growth of the German economy: in Prussia, between 1867 to 1860, 88 of them were founded; between 1870–1873, 928 were founded.[11][12] However, as discussed prior, its beginning date has been placed as far earlier; any periodization includes Germany and Austria-Hungary's rapid economic development.

A decisive factor in this rapid economic development was the construction of new railways. Typical “founders” were therefore railway entrepreneurs such as Bethel Henry Strousberg. Railroads had a significant stimulating effect on other branches of industry, for example through the increased demand for coal and steel, so that industrial empires such as that of Friedrich Krupp emerged during the Gründerzeit. Mass production of non-industrial goods, such as foodstuffs, was made possible during this period by the birth of railroads. Perhaps most importantly, communication and migration were made much easier. Rural lower classes migrated en masse to the cities, where they became part of the emerging proletariat: in Germany, the expanded Gründerzeit was the time in which the social question was first addressed by socialists.

Reparations payments from the French Third Republic were enormously stimulating to the German economy. The five billion gold Francs which the French state agreed to send were melted down and recast as gold Marks. Simultaneously, the new German state sold off its silver reserves and bought more gold on the world market. To counteract a devaluation of the silver currencies caused by the high amount of silver on the market, France was forced to limit the minting of silver coins (see Latin Monetary Union).

German writers of the late 19th century used the term Gründerzeit as a pejorative, because the cultural output of that movement was associated with materialism and nationalistic triumphalism. Cultural historian Egon Friedell complained that fraud in the stock market had not been the only swindle of the Gründerzeit, lambasting greater cultural trends of the time.[13]

Design and architecture

[edit]The need for housing rose in consequence of industrialization. Complete housing developments in the so-called Founding Era's Architecture style arose in previously green fields, and even today, Central European cities have many buildings from the time together along a single road or even in complete districts. The buildings have four to six stories and were often built by private property developers. They often sported richly-decorated façades in the form of Historicism such as Gothic Revival, Renaissance Revival, German Renaissance and Baroque Revival. Magnificent palaces for nouveau-riche citizens but also infamous rental housing for the expanding urban lower classes were built.

The period was also important for the integration of new technologies in architecture and design. A determining factor was the development of the Bessemer process in steel production, which made possible the construction of steel façades. A classical example of the new form is the steel and glass construction of the Crystal Palace, completed in 1851, which was then revolutionary and inspired subsequent decades.

Gründerzeit districts, called Gründerzeitviertel, were built all over Germany, Austria and even in Hungary. In the German-speaking world, the architecture of the Gründerzeit would be supplanted by Jugendstil in the early 20th century.

- Examples of Gründerzeit districts

In Austria

[edit]In Austria, the Gründerzeit began after 1840 with the industrialisation of Vienna, as well as the regions of Bohemia and Moravia. Liberalism reached its zenith in Austria in 1867 in Austria-Hungary and remained dominant until the mid-1870s.

Vienna, the imperial capital and the residence of Emperor Franz Joseph, after the failed uprising of 1848 became the fourth-largest city in the world with the inclusion of suburbs and an influx of new residents from other regions of Austria. Where the city wall had once stood, a ring road was built, and ambitious civic buildings, including the Opera House, Town Hall, and Parliament, were also built. In contrast to agricultural workers and urban labourers, an increasingly-wealthy upper-middle class installed monuments and mansions. That occurred on a smaller scale in other cities such as Graz but on the periphery, which preserved the old city from destructive redevelopment.

In Germany

[edit]

In the mindset of many Germans, the epoch is intrinsically linked with Kaiser Wilhelm I and Chancellor Bismarck, but it did not end with them (in 1888 and 1890, respectively) but continued well into the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II. It was a Golden Age for Germany in which the disasters of the Thirty Years' War and the Napoleonic Wars were remedied, and the country competed internationally in the areas of science, technology, industry and commerce. Particularly, the German middle class rapidly increased its standard of living, buying modern furniture, kitchen fittings and household machines.

In German-speaking areas, a huge number of publications were produced that was comparable, on a per-capita basis, to modern levels. Most were academic papers or scientific and technical publications, often practical instruction manuals on topics such as dike construction. There was no copyright law in most countries except in the United Kingdom. Since popular works were immediately republished by competitors, publishers needed a constant stream of new material. Fees paid to authors for new works were high and significantly supplemented the incomes of many academics. The prices of reprints were low and so publications could be bought by poorer people. A widespread public obsession with reading led to the rapid autodidactic dissemination of new knowledge to a broader audience. After copyright law gradually became established in the 1840s, the low-price mass market vanished, and fewer but more expensive editions were published.[14][15]

The social effects of industrialisation were the same as in other European nations. Increased agricultural efficiency and introduction of new agricultural machines led to a polarized distribution of income in the countryside. The landowners won out to the disadvantage of the agrarian unpropertied workforce. Emigration, most of it to America, and urbanisation were consequences.

In the rapidly-growing industrial cities, new workers' dwellings were erected, lacking in comfort by today's standards but criticised even then as unhealthy by physicians: "without light, air and sun", they were quite contrary to the prevailing ideas on town planning. The dark, cramped flats took much of the blame for the marked increase in tuberculosis, which spread also to wealthier neighbourhoods.

Nevertheless, the working class also saw improvements of living standards and other conditions, such as social security through laws on workers' health insurance and accident insurance introduced by Bismarck in 1883–1884, and in the long run also through the foundation of a social democracy that would remain the model for the European sister parties until Hitler's Machtübernahme in 1933. Even today, the model of social care developed by Bismarck in 1873 (Reichsversicherungsordnung) remains the contractual basis for health insurance in Germany.

References

[edit]- ^ Hackbarth, Freddy H. (1 April 2024). "Leitartikel: Was ist die Gründerzeit?". Faszination Gründerzeit (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ "Wie ein Börsencrash 1873 die Gründerzeit beendete". capital.de (in German). 27 May 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Horn, Gustav A. "Definition: Gründerjahre". wirtschaftslexikon.gabler.de (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische (13 April 2016). "Das Kaiserreich als Nationalstaat". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Deutschland, Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum, Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik. "Gerade auf LeMO gesehen: LeMO Das lebendige Museum Online". www.dhm.de (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Judson, Pieter (2016). The Habsburg Empire: A New History. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0674047761.

- ^ "Gründerzeit und Nationsbildung 1849 – 1871". Seminarbuch Geschichte (in German). doi:10.36198/9783838532530. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Bildung, Bundeszentrale für politische. "Kondratieff-Zyklen". bpb.de (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ serviceplan (16 July 2019). "GLINT - Gründerzeit: Erfahren Sie mehr über die Geschichte des Hauses". GLINT (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ "Gründerzeithaus – Gründerzeithaus" (in German). Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ "Wie ein Börsencrash 1873 die Gründerzeit beendete". capital.de (in German). 27 May 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ "Historische Finanzkrisen (3): Das abrupte Ende der Gründerzeit begann an der Donau". FAZ.NET (in German). 8 March 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Matthew Jefferies (2020). Imperial Culture in Germany, 1871–1918. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 9781137085306.

- ^ Thadeusz, Frank (18 August 2010). "No Copyright Law: The Real Reason for Germany's Industrial Expansion?". Spiegel Online.

- ^ Lasar, Matthew (23 August 2010). "Did Weak Copyright Laws Help Germany Outpace The British Empire?". Wired.

Further reading

[edit]- Baltzer, Markus (2007). Der Berliner Kapitalmarkt nach der Reichsgründung 1871: Gründerzeit, internationale Finanzmarktintegration und der Einfluss der Makroökonomie (in German). Münster: LIT. ISBN 9783825899134.

- Hermand, Jost (1977). "Grandeur, High Life und innerer Adel: 'Gründerzeit' im europäischen Kontext". Monatshefte (in German). 69 (2): 189–206. JSTOR 30156817.

External links

[edit] Media related to Gründerzeit architecture in Germany at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gründerzeit architecture in Germany at Wikimedia Commons